Learn More

amfAR Policy Briefs

Title X, the Domestic Gag rule, and the HIV Response

February, 2019

The Title X National Family Planning Program is the only federal grant program dedicated to providing individuals with comprehensive family planning and related health services. Created in 1970, Title X offers care to low-income or uninsured individuals through the provision of grants to public health departments, community health organizations, and other nonprofit agencies. By providing women, their partners, and their families with a range of birth control methods, cancer screening, and other reproductive health services, Title X funding reduces unintended pregnancies, allows the early diagnosis of potentially deadly cancers including breast and cervical cancers, and promotes healthy child development.

On June 1, 2018, the Trump Administration proposed a rule change to Title X stating that health care providers in the program may not “perform, promote, refer for, or support, abortion.” On February 22, 2019, The Department of Health and Human Services posted a draft of the final rule, which would take effect 60 days to a year after its publication in the Federal Register—which is pending. Using Title X funds for abortion has been prohibited since the inception of the program. As such, the Administration’s rule (the so-called ‘domestic gag rule’) does not regulate the provision of abortion services, but rather limits the ability of health care providers to deliver information on the full scope of legally available medical services and dictates the types of care that organizations may provide using their own financial resources.

This brief addresses the role of Title X providers in the HIV care, and the extent to which the rule may affect access to HIV services.

The brief is available here.

Toward an Effective Strategy to Combat HIV, Hepatitis C and the Opioid Epidemic: Recommendations for Policy Makers

April 2018

Mitigating the long-term harms for people with substance use disorders will require a multifaceted strategy that increases access to treatment, reduces the risk of HIV and hepatitis C acquisition, and lowers the risk of fatal drug overdoses. This report describes a set of recommendations to accomplish these aims.

The report is available here.

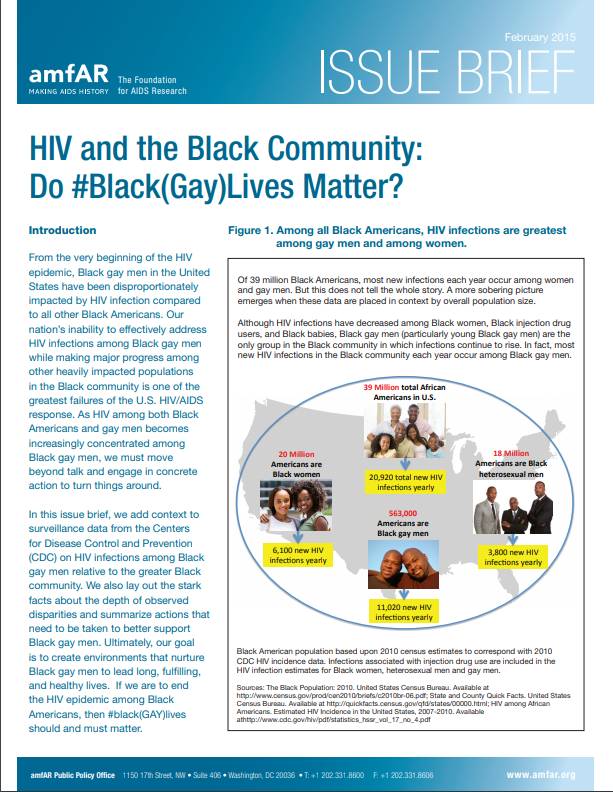

HIV and the Black Community: Do #Black(Gay)LivesMatter?

February, 2015

From the very beginning of the HIV epidemic, Black gay men in the United States have been disproportionately impacted by HIV infection compared to all other Black Americans. Our nation’s inability to effectively address HIV infections among Black gay men while making major progress among other heavily impacted populations in the Black community is one of the greatest failures of the U.S. HIV/AIDS response. As HIV among both Black Americans and gay men becomes increasingly concentrated among Black gay men, we must move beyond talk and engage in concrete action to turn things around.

In this issue brief, we add context to surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on HIV infections among Black gay men relative to the greater Black community. We also lay out the stark facts about the depth of observed disparities and summarize actions that need to be taken to better support Black gay men. Ultimately, our goal is to create environments that nurture Black gay men to lead long, fulfilling, and healthy lives. If we are to end the HIV epidemic among Black Americans, then #black(GAY)lives should and must matter.

The report is available here.

Additional Resources

Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States

February 7, 2019

In the State of the Union Address on February 5, 2019, President Donald J. Trump announced his administration’s goal to end the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years. The president’s budget will ask Republicans and Democrats to make the needed commitment to support a concrete plan to achieve this goal. While landmark biomedical and scientific research advances have led to the development of many successful HIV treatment regimens, prevention strategies, and improved care for persons with HIV, the HIV pandemic remains a public health crisis in the United States and globally.

Fauci, A., Redfield R., Sigounas, G., et al., JAMA. 2019:321(9):844-845. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.1343

HIV Testing in 50 Local Jurisdictions Accounting for the Majority of New HIV Diagnoses and Seven States with Disproportionate Occurrence of HIV in Rural Areas, 2016–2017

June 28, 2019

Since 2006, CDC has recommended universal screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection at least once in health care settings and at least annual rescreening of persons at increased risk for infection (1,2), but data from national surveys and HIV surveillance demonstrate that these recommendations have not been fully implemented (3,4). The national Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative* is intended to reduce the number of new infections by 90% from 2020 to 2030. The initiative focuses first on 50 local jurisdictions (48 counties, the District of Columbia, and San Juan, Puerto Rico) where the majority of new diagnoses of HIV infection in 2016 and 2017 were concentrated and seven states with a disproportionate occurrence of HIV in rural areas relative to other states (i.e., states with at least 75 reported HIV diagnoses in rural areas that accounted for ≥10% of all diagnoses in the state).† This initial geographic focus will be followed by wider implementation of the initiative within the United States. An important goal of the initiative is the timely identification of all persons with HIV infection as soon as possible after infection (5). CDC analyzed data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)§ to assess the percentage of adults tested for HIV in the United States nationwide (38.9%), in the 50 local jurisdictions (46.9%), and in the seven states (35.5%). Testing percentages varied widely by jurisdiction but were suboptimal and generally low in jurisdictions with low rates of diagnosis of HIV infection. To achieve national goals and end the HIV epidemic in the United States, strategies must be tailored to meet local needs. Novel screening approaches might be needed to reach segments of the population that have never been tested for HIV.